Por: Hugo Córdova Quero

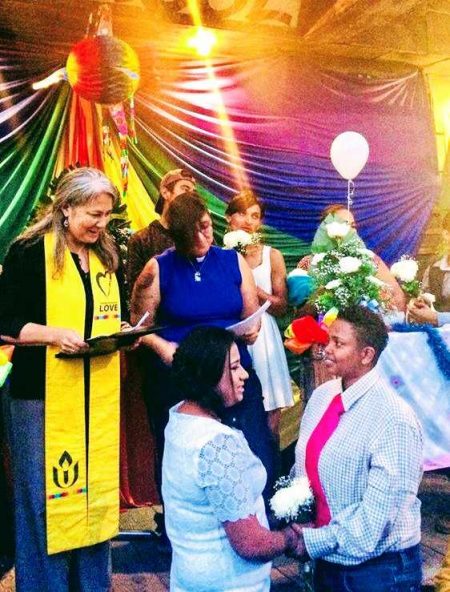

Foto: Rev. Ranwa Hammady, 2018

Introduction

From November 16 to 19, I was part of a committee of the Justice Commission of California of the Unitarian Universalist Church that traveled from San Diego, United States of America, to Tijuana, Mexico. I was sent by Starr King School for the Ministry, at the Graduate Theological Union, where I am Visiting Associate Professor of Critical Theories and Queer Theologies. Among the ten participants, four of us are ordained ministers. Although planned for a long time, the event could not anticipate the arrival of caravans of Central American migrants to Tijuana, which mobilized a large number of volunteers to accompany and provide hospitality to the more than 9,000 people arriving in that city. The delegation of which I was a part immediately joined these efforts to serve our migrant sisters and brothers. Among the people who started the trip was a caravan of eighty-four LGBT people who were the first to arrive in Tijuana. Their lives and experiences reflect common elements with other modern migrations.

Let us keep in mind that contemporary migrations are a phenomenon intrinsically associated with capitalism. They provide cheap labor for the continuation of the production of goods and services within the world-system. The displacement of people —both voluntary and forced— has become even more visible in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and has already begun to mark the first decades of the present century. Although migrations have the economy as a significant factor, this is not the only reason why people leave their place of origin to settle in a different context. Especially in forced migrations, hunger, wars, persecutions —political, religious, ideological—, gender or sexual orientation are also prevailing reasons for the displacement of people. In this essay, I focus specifically on the experience of the Honduran people who make up the majority of the LGBT caravan in Tijuana.

The Honduran context

Honduras is not an exception to the situation of forced displacement of people and communities. A member of the so-called “northern triangle,” Honduras together with Guatemala and El Salvador make up a region of economic exchange but also of shared violence. That fact is demonstrated in the rate of violent deaths in the area that exceeds deaths in war zones in other parts of the world, according to the reports of the United Nations (UN) (Prensa Libre, 2012). The increase in drug trafficking, the presence of allies to the Mexican cartels, and the weakness of democratic institutions have produced a rarefied social climate that leads to marked violence (Prado Pérez, 2018). Violence also increases with the incipient presence of weapons and a young generation that is practically unemployed (UNODC, 2012, 2013). The coup d’état against President Manuel Zelaya in 2009 precipitated the conditions for the development of structural violence. The election of President Porfirio Lobo did not produce the expected results, as several countries in the region and Latin America did not recognize the electoral process. Little by little some countries changed their position although not all members of the Organization of American States (OAS) acknowledge it today. One of the highlights of this situation was that the former secretary of the State Department of the government of the United States of America, Hillary Rodham Clinton, declared in her book Hard Choices (2014) that her role was to organize —together with other authorities in the region— an electoral process that prevented the return of Zelaya to the presidency. Interestingly, the United States of America is the country that today most opposes forced immigrants as a result of these political decisions. The promotion to the presidency in 2014 of Juan Orlando Hernández did not change the political situation in Honduras.

Although the Mayan culture flourished in its territory, Spanish colonization from the sixteenth century to modern neo-colonial processes produced the structural impoverishment of Honduras. In its history, the country had another coup in 1962, which plunged society into a military dictatorship that lasted until 1981. The nine million inhabitants who now reside in the state have suffered other situations, with the result of hardening their living conditions — for example, the incipient deforestation, and its consequent climatic changes as well as the contamination of the water resulting from the ruthless mining activity by transnational companies.

Honduran society has also suffered the prevalence of the Roman Catholic Church with its conservative moral stance and the successive government by right-wing parties. All this has produced a climate that is not tolerant of diverse racial- and gender-dissident groups.

The 2018 migrant caravan(s) and LGBT people

The Honduran caravan is not the only one that occurred in October 2018 in Central America. While it is true that the first caravan left from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, on October 13 and was composed of about a thousand people, soon others followed. The LGBT caravan was a group of people that broke away from this first caravan.

The second caravan left from Esquipulas, Guatemala, on October 21. The third caravan left from San Salvador, El Salvador, on October 29. The fourth caravan also departed from San Salvador on October 31. Finally, the fifth caravan started its journey on November 5, also from El Salvador. The LGBT caravan arrived first in Tijuana and was composed mostly of people from Honduras.

These caravans of people forced to leave their place of origin due to precarious living conditions and violence are not the only signs of the Central American exodus to other lands; their reasons are multiple. For decades abandoned girls and boys have embarked on leaving their place of origin while women fleeing gender violence and human trafficking have also begun that same journey. So far in 2018, 50,036 girls and boys —mainly from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador— have been apprehended by the US Border Guard (US Custom and Border Patrol, 2018).

People of sexual diversity are another visible group in this displacement of people that cannot be explained merely by economic issues. There is a combination of factors that affect people in different ways and results in their migration. The structural causes are multiple, and the solutions to their situations cannot ignore this fact. A policy that only focuses on the economy condemns —from the outset— the future of people to failure because economic precariousness is not the only variable in this complex process. In the case of LGBT people in the Honduran caravan, this is more than evident. Silvia Soriano Hernández and Víctor Hugo Gutiérrez Albertos (2016-2017) explain that situation in the following manner:

Today’s society suffers from great inequalities, and it is common that these lead to discriminatory attitudes that manifest themselves in multiple forms ranging from contempt and ridicule to violent aggression that can lead to murder. We can begin by citing the economic discrepancies that result in few beneficiaries in front of a large group of dispossessed, both work and basic goods. We add the differences that appear depending on the color of the skin or the sex with which it is born as well as the sexual preferences of every individual (p. 90).

As soon as the caravan left Honduras, frictions between heterosexual and LGBT people became evident precisely because the same attitudes and stereotypes learned in the society of origin were reproduced in the movement. Those situations are even more violent in the case of transgender people. In this regard, Soriano Hernández and Gutiérrez Albertos (2016-2017) point out the excessive violence that transgender people experience and their mechanisms of resistance:

[…] based on their status as discriminated against, they opt for militancy in the struggle for their rights as a collective and the adversities they must overcome, including death threats, including beatings, insults, and various disqualifications. The incomprehension about their self usually begins in their family nucleus and extends to all the frequented places, the school, the neighborhood, the work, etcetera. What we can advance is that despite the discrimination and repression from violent to symbolic forms, people who choose to break away with the normativity of sex-gender binarism must face many obstacles that can lead to concealment. However, not everyone decides to remain in silence or invisibility, and they are the ones that offer us a guideline for the recognition of rights that if not required, are not granted (p. 91).The testimonies of the eighty-four people of the Honduran LGBT migrant caravan are graphic in the description of their situations. For example, Lady Perez, a transgender twenty-three years old Honduran woman, said in an interview for the BBC that it was the murder of her partner that motivated her to leave her country:

They murdered him because he was with me, because of his sexual preference. It was a day that accompanied me to take a taxi. Some guys came to a stop, and there they shot him. They also killed two people who were also there. I survived by a miracle (Rojas, 2018).

Honduras has the highest rate of murders of transgender people in the region. However, this is not indicative that other people who joined the caravan from El Salvador or Guatemala have not experienced violence in one way or another. Ana Gabriela Rojas (2018) recovers another story:

Loli, a 26-year-old transgender woman from El Salvador, shows her doll: she has a scar that a man with a machete made in a restaurant. […] In her leg she has another mark of the attack of an unknown person perpetrated “simply because of homophobia.”

The common denominator of LGBT people in the migrant caravan is the effects of the structural violence in society that based on homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia, and transphobia. That situation produces hate crimes that often result in irreversible consequences, such as death.

As I mentioned earlier, in the midst of the caravan to the United States of North America, LGBT people were victims of multiple situations of violence. On this, Erick Alexander Durán Reyes, one of the members of the LGBT caravan, states: “We were discriminated against, even in the caravan. […] People wouldn’t let us into trucks, they made us get in the back of the line for showers, they would call us ugly names”(Drury, 2018).

For her part, Lady Pérez also describes this situation: “They have denigrated us, you are supposed to be migrating from your country because of violence and discrimination, homophobia, and it turns out that in the same caravan you find that violence” (Frontera. Info, 2018).

Finally, when they arrived in Tijuana, they were also discriminated by some people after, with the help of lawyers, the group was able to rent a house to stay. In the midst of a protest against the LGBT caravan —in which people even threw stones— Patricia Elena Juárez Hernández, a Tijuana resident, said: “We are surprised, shocked, uncomfortable because the authorities did not consider us. Here is a municipal president, a delegation that should have told us: neighbors, we ask for your support, your collaboration, these people will come” (Martín-Fradejas, 2018). A few days later, the caravan had to move to other places and keep its location secret due to the fear that LGBT people could face further attacks.

The seven LGBT weddings

In the midst of the task of distributing clothes, preparing food, and heating tortillas, the ministers of the Unitarian Universalist delegation, received an unusual request: “They are talking about getting married and ask that the ministers go to the third floor.” The one who summoned us was a person from the Enclave Caracol center, an LGBT friendly space located in downtown Tijuana. The center had enabled its building as a shelter until the people of the LGBT caravan could be relocated elsewhere. When we went up to the third floor, we found a group composed of several couples.

One of the things that we worried about when asked to officiate the ceremonies was to respect not only the particular faith of each person to marry but also to consider the elements that they deemed necessary for these ceremonies to be meaningful in their lives. It was essential to know, for example, that each person in the group identified as evangelical and not as a Roman Catholic. Accustomed in our churches to respect the diversity of faith of each person, the ministers —Rev. Ranwa Hammady, Rev. Leslie Takahashi, Rev. Mar Cárdenas Loutzenhiser, Rev. Rodney Lemery and I— decided to write a ceremony that was as respectful as possible to what the couples wanted. The first question they asked us was if they were going to be able to exchange rings. The second question was about whether you could have witnesses —madrinas and padrinos—, and the last one was about the use of bouquets.

Apparently, for the couples, it was imperative to have the cultural symbols that would characterize the event like a wedding and not as a political declaration. Although in the countries of origin, neither legal nor ecclesial weddings are allowed for LGBT persons, two critical elements came together in Tijuana. On the one hand, the fact that Tijuana has legislated as legally valid weddings between LGBT people in 2015. On the other hand, the reality that —different from the Roman Catholic Church— many Christian churches currently conduct ceremonies of same-sex marriage. The ministers present are part of churches that do not discriminate against people in the sacrament of marriage, neither because of their gender, their sexual orientation, their gender identity, or their biological sex. This situation generated an expectation and joy among the people who got married. Pedro Nehemías Pastor de León, who married Erick Alexander Durán Reyes, expressed it this way: “This is a dream come true because you do not see it in our countries of origin. It is something we had always wanted to do, and just today we had the opportunity to carry it out” (Azteca America, 2018).

Thus, with the support of Enclave Caracol center, Garymar Center of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Tijuana, and other donations, soon people went out to buy rings, flowers, and cakes; while other people arranged an altar with a huge rainbow flag as background. The ministers began to plan a marriage liturgy and write marriage certificates.

At 4 pm on November 17, a gay couple, two lesbian couples, three transgender couples and a heterosexual couple went up the stage —one by one— to exchange vows and rings and throw the bouquet to the people present. The rain of rice, streamers, confetti, and the shouts of joy of those who witnessed the weddings were a blessing that encouraged each couple to say, “yes.”

The press reporting the event did not manage to capture the most critical aspect of this historical fact. For the most part, the news qualified weddings simply as “marriages” or “symbolic weddings,” which is wrong. Putting the word “marriage” in quotation marks denotes the fact that people of sexual diversity do not unite in a real marriage, but that their union is questionably a “marriage.” At the same time, when speaking of “symbolic weddings” the sacramentally valid character of these unions —legitimized, respected and recognized by the present churches which even granted a marriage certificate— is questioned.

It is evident that for many people in the media the hegemonic ideology that still prevails dictates that marriage is only between cis-heterosexual women and men and that only the unions blessed by the Roman Catholic Church are sacramentally valid. That situation is profoundly dismissive of the diversity of positions within the Christian religion in which many churches do not embody homophobia, lesbophobia or transphobia. In the end, the way in which the media reported the weddings put once again LGBT people in a second-class position and questions the validity of unions between same-sex couples.

Those of us who officiate at the marriage ceremonies close the marriage ceremony with these words:

Today you have marked a historic milestone because we have done weddings for real. Do not let anyone question the validity of your marriage or tell them that these weddings are “false.” The ministers and ministers here present are authorized and authorized by our churches to marry every person who so wishes and that this wedding is sacramentally valid. You have come a long way to reach this place, not only in your relationship as couples but also geographically. They have left loved ones and left their homeland to look for a better tomorrow. Do not allow anyone to take away their dignity. Today you have also been prophetic in announcing to the world that in the midst of despair and the many things that await them in the future, only love will make you stronger. That they have walked for so many days so many miles to tell the world that their love is true is already an act of hope, an act of resistance and political action. In Christian traditions, there are no churches or ministers who marry the couples, but rather the individuals involved are the ones who marry each other. We, ministers, are witnesses to honor and respect your marriage. We want you to be happy and that God bless you today and always.

This essay began with the words “love is strong,” from the homonymous song written in 1993 by Fernando Barrientos and Daniel Martín. Although their song speaks that “the world has been split in two while dreams bleed for nothing,” the LGBT couples who married affirm and enhance their message that —after everything they have been through— their “love is strong.” It is —perhaps in the midst of everything that an in/migrant has to go through to move forward— that our affections and our hopes become stronger as the love shown in each couple that got married. The weddings of the LGBT people of the Honduran caravan are an act of justice in the midst of the many injustices that migrants face. The way in front of them in their sexile request —asylum because of persecution due to sexual orientation (Guzmán, 1997)— is marked by the geopolitics of modern migratory processes. It only remains for us to wait for justice to come true and that the eighty-four members of the LGBT caravan can leave behind a past of persecution.

References

Clinton, Hillary (2014). Hard Choices. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Drury, Colin (2018). “Gay Couple From Migrant Caravan Marry as They Arrive in Mexico-US Border Town.” The Independent, November 18. Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/migrant-caravan-gay-couple-wedding-mexico-us-central-america-tijuana-lgbt-a8639986.html>, accessed on November 27, 2018.

Frontera.Info (2018). “Comunidad LGBT de caravana migrante refiere violencia y discriminación,” November 13. Available at: <https://www.frontera.info/Internacional/2018/11/13/1387419-Comunidad-LGBT-de-caravana-migrante-refiere-violencia-y-discriminacion.html>, accessed on November 27, 2018.

Guzman, Manuel (1997). “Pa’ La Escuelita con Mucho Cuida’o y por la Orillita’: A Journey through the Contested Terrains of the Nation and Sexual Orientation.” In: Puerto Rican Jam: Rethinking Colonialism and Nationalism, edited by Frances Negron-Muntaner and Ramon Grosfoguel. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 209-228.

Prado Pérez, Ruth Elizabeth (2018). “El entramado de violencias en el Triángulo Norte Centroamericano y las maras.” Sociológica 33, No. 93 (January-April): pp. 213-246.

Prensa Libre (2012). “Triángulo Norte es una de las zonas más violentas del planeta”. Prensa libre.com, September 27. Available at: <https://web.archive.org/web/20140529061409/http://www.prensalibre.com/internacional/Triangulo-Norte-zonas-violentas-planeta_0_781722003.html>, accessed on November 27, 2018.

Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito (ONUDC) (2012). Delincuencia organizada transnacional en Centroamérica y el Caribe: Una Evaluación de las Amenazas. New York, NY: ONUDC.

Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito (ONUDC) (2013). Estudio mundial sobre le homicidio: tendencias, contextos y datos. New York, NY: ONUDC.

Rojas, Ana Gabriela (2018). “Caravana de migrantes en Tijuana: ‘Salí de Honduras porque mataron a mi pareja por homofobia’, la violencia que persigue a las transexuales de Centroamérica.” BBC News, November 23. Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-46317956>, accessed on November 27, 2018.

Soriano Hernández, Silvia and Víctor Hugo Gutiérrez Albertos (2016-2017). “Entre la muerte y la fuga. Diversidad sexual acosada”. Díkê: Revista de Investigación en Derecho, Criminología, y Consultoría Jurídica 10, No. 20 (October-March): pp. 89-110.

US Custom and Border Patrol (2018). “U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018”. Available at: <https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions>, accessed on November 27, 2018.